Chapter 16: How to listen the right way

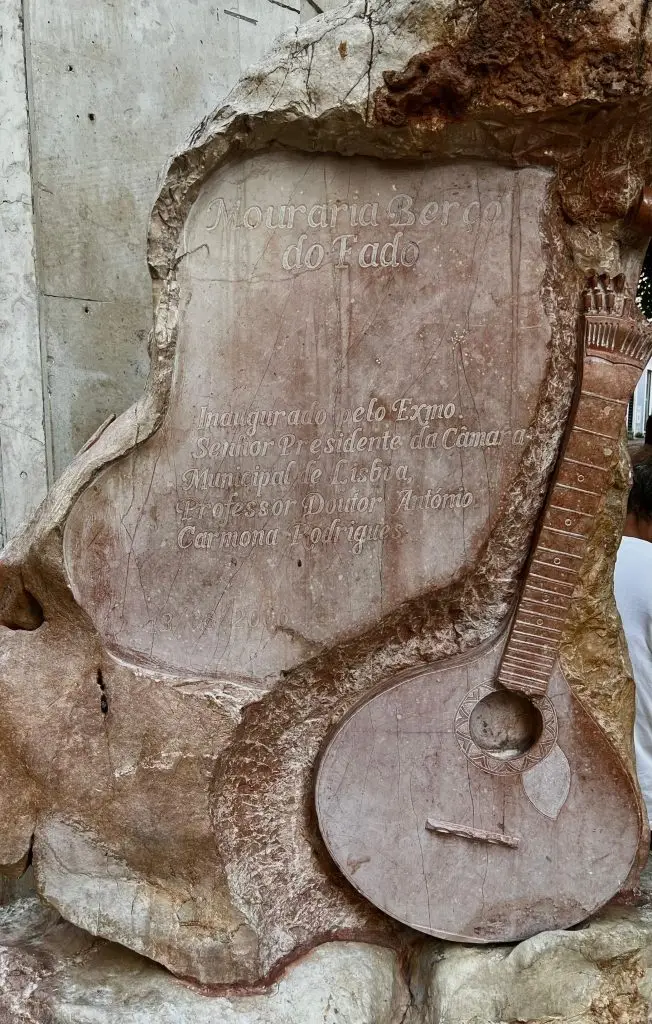

The most authentic Fado show in the city – is a promotion slogan that you will read so many times in one place that you wonder: Which of them tells the truth? And what does authentic Fado really mean? A key part of it is the strong connection to tradition, which is mirrored in the long history of Fado.

Traditionally, Fado is sung in restaurants, combined with gastronomy. And thus, some artists, as Sara Paixão and Pedro Moutinho, find that only in the Fado houses one can experience authentic Fado. Nevertheless, it happens that the food in the restaurants keeps people from appreciating the music as much as it deserves to be. This is why Fado singer Nadine prefers to perform at concert venues.

Fado house or concert venue?

Filipa Biscia plays at different kinds of venues. She likes performing in both restaurants as well as at other evening shows. A night in a Fado house is more exhausting for her as an artist, but she also admits that it’s the more authentic way of experiencing Fado. However, she thinks that a concert outside a Fado house is an authentic experience, too – as long as the artists are authentic fadistas.

In the end, it depends on the personality of the listeners which kind of experience might be best for them. There is red and white wine, some prefer dry, and others prefer a fruity one. On the same note, there are different tastes of Fado.

Each of the “chefs” – the Fado singers – has their own way of creating a taste and each guest has their individual preferences. Thus, it is impossible to describe a Fado show objectively as a good or a bad experience. It might have been good or bad for oneself, but there will always be someone who would think the contrary. Some people might prefer a female over a male voice, prefer an A Capella show over a performance with microphone.

Also, the ‘way of tasting’, may vary among the Fado audience. In all the individuality we shouldn’t forget some manners of behavior everyone should stick to.

Tradition no. 1: Don’t try to understand, just feel.

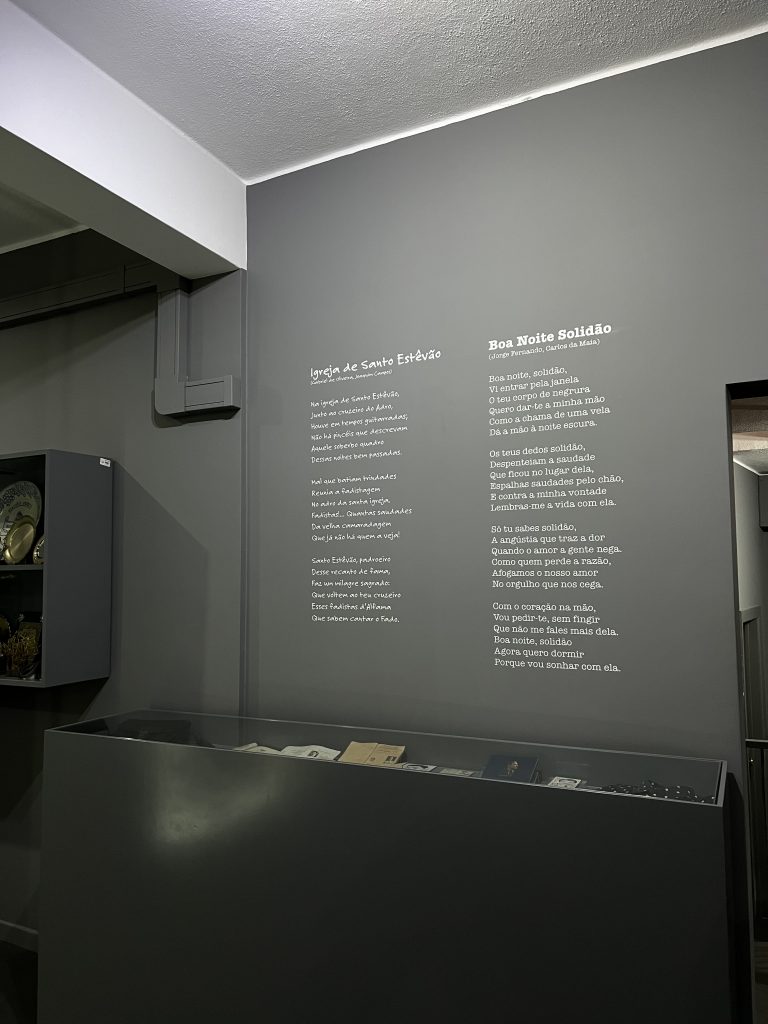

Rather than understanding each part of the lyrics, the sparkle of Fado lies in the feelings vibrating through a room when it’s sung. The feelings sent out from the musicians as well as the feelings of the listeners. Therefore, a fadista shouldn’t feel the need to explain a song, it should simply be felt. Let the magic happen.

Tradition no. 2: Respect the silence.

Restaurants are places to eat, to laugh and to talk – in Fado restaurants, there are the sets of Fado determining the structure of a dinner night. And while the artists present Fado, everyone else got to be quiet – it’s the only way to listen well. In most fado houses silence during the Fado is being respected. However, there are always exceptions, depending on the restaurant and the audience. An example out of my ‘fado diary’:

Somehow accidently, I step into the Tasca de Noticias restaurant, located in the Bairro Alto. It’s one of those places that tries to attract tourists with promoting “live Fado performances”. I enter without any expectation, in the need for water and some sweet dessert. The waitress is super friendly. The problem is that she is friendly even when the Fado is played. I feel like doing something illegal when I talk to her after she came up to me to take my order. Even guitar player and singer Luis Tomar, who plays on that evening, tells me that he does not consider this a real Fado house. After having played all around the world, he is at the end of his career, thus he doesn’t have high expectations on the space he plays. He still shares his doubts to the waiters, but they are more focused on being kind to each guest.

My individual experience

Therefore, Tasca de Noticias a good place to have dinner. The Fado played there is good too. But the ambient of the restaurant doesn’t respect the Fado tradition in the right way.

Tradition no. 3: Listen with your ears, see with your eyes

When experiencing special moments, it has become a usual pattern of humans to take out their phone and take a photo or a video of the scene happening around them. This kind of behavior shifts our mental focus from perceiving the presence with one’s own senses to the effort of getting the best picture out of the moment. People want proof of having been there, but the problem is that those people might disturb those who keep saving their memories in their souls – it happened to me, in one of the most famous Fado venues in Lisbon.

Located in an almost majestic position, Café Luso overlooks the Rua do Norte of Bairro Alto. “Like a dining room of a king’s palace” are the first words in my notes. It’s the piano in the entry hall, the high ceilings, the candlelight on the walls behind the Fado musicians that make this room look so majestic. Also, in addition to the guitars there is a Cello adding a little extra point to the Fado in this venue. I sit on a small table right next to the bar, in front of me are two rows of tables. At their end, there is the musicians’ space. I only have a few seconds to admire the great Cello until a man on the table in front of mine stands up from his chair – he moves to the middle, rises both his arms with the phone in his hand. As he sits down, I see how he reviews the pictures he has taken before. They still don’t seem to be good enough, as he keeps on taking pictures, standing up and sitting down again. I cannot believe his audacity to behave that way. He makes it impossible for me to focus on the Fado happening in the front.

My individual experience

In the break before the last Fado set I overhear a conversation between some young women who share their amazement about the night, which has been their first Fado experience, with one of the organizers at the restaurant. He explains to them that according to a Portuguese saying they themselves have transformed into fadistas only through listening well to it (“E tao Fadista quem Canta Como quem sabe Escutar”). And it makes me think again of the man taking pictures, who has not been able to listen well, thus doesn’t deserve the title of a fadista…

Let the magic happen

Of course, it is nice to keep a memory together with a souvenir in our camera roll. However, when it comes to live music, it is not our phone but rather our heart that will keep the energy and the memories from the experience in the best way possible. To keep the listeners experiencing a Fado show with their soul rather than through the camera lenses and in respect to the artists, some Fado houses don’t allow to take videos or even photos during the performance. Nevertheless, in many restaurants it is still officially allowed; and that’s okay, as long as one does it consciously and with respect towards the musicians and other guests.